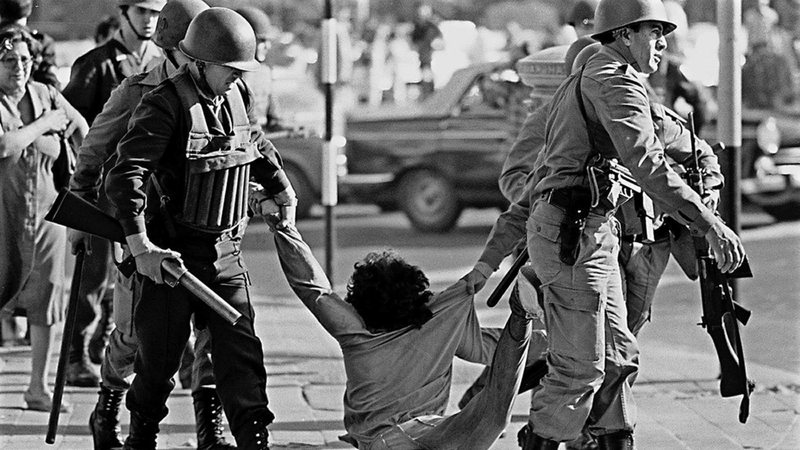

This is not March 31 like any other. After reaching the sad mark of more than 300,000 Brazilian victims of the Coronavirus and being immersed in the greatest health collapse in our history and in a political crisis, it is still necessary to fight for democracy in a country governed by the extreme right.

March 31: Nothing to celebrate

The increasing militarization of the Bolsonaro government and the risks of this phenomenon to Brazilian democracy

President Bolsonaro (no party), throughout his public career, has always presented strong links with the military class. The chief executive vehemently affirms his pride in assembling a management, in his words, “completely militarized”.

Constitutional guarantees in conflict? The limits of freedom of expression and the abuses of immunity of the Brazilian parliamentarians

On February 16, 2021, Daniel Silveira was arrested after he published on YouTube a video of almost 20 minutes in which the deputy makes threats and offends the honor of the ministers of the STF (Supreme Federal Court), besides propagating the adoption of antidemocratic measures against the court. He also defended AI-5, the institutional act that marked the beginning of the harshest period of the Brazilian military dictatorship.

Alexandre de Moraes, the STF minister who ordered the arrest of the deputy, said that Silveira’s remarks in the video instigate violent actions against the security of the STF ministers, violating the National Security Law. Moraes also pointed out that Silveira is a “repeat offender” and said that the deputy’s remarks were a “clear affront to the principles of democracy, republic and the separation of powers.

Silveira’s defense contests the legality of the deputy’s arrest and argues that the Supreme Court’s decision is an attack on the freedom of expression, stating that “The facts that formed the basis of the declared arrest do not even constitute a crime, since they are protected by the inviolability of words, opinions and votes that the Constitution guarantees to federal deputies and senators”. Nevertheless, on February 19, 2021, the Chamber of Deputies kept Silveira in prison by a large majority.

Faced with such a case, we must question the limits of freedom of expression and the protection guaranteed by parliamentary immunity.

Freedom of Speech: Can it be abused?

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right and is guaranteed by Article 5 of the 1988 Federal Constitution. The guarantee of this right was a major step forward after the military dictatorship, a period when the manifestation of ideas and opinions was intensely and violently repressed by the state.

The debate about the separation between freedom of speech and hate speech is cyclical and was brought to the fore with the recent events of Daniel Silveira’s arrest and the consequent discussions about parliamentary immunity. There are those who argue that this right has been used as a shield for speeches that threaten democracy and for the uttering of hateful words.

One of the characteristics of fundamental rights is the fact that they depend on the moment of their application. Which right will prevail is a question that must be defined in each concrete case. The STF has decided that “There are no, in the Brazilian constitutional system, rights or guarantees that have an absolute character.” The best way to rescue what was argued by the STF is that an adequate interpretive process must be developed for a fundamental right to triumph in the application of a case. Therefore, the right to freedom of expression, being a fundamental right, does face limits, despite being essential to democracy.

Taking the case of Daniel Silveira as an analysis, a debate arises to discuss whether the deputy’s speeches are within his right of freedom of speech and protection of parliamentary immunity, as his defense claims, or whether the deputy is, in fact, using this fundamental right as an excuse to hurt democracy and make threats to the ministers and the institution of the STF.

Justice Alexandre Moraes defended that, although freedom of expression is a constitutional guarantee, the manifestations that have the purpose of “controlling or even annihilating the strength of critical thought, indispensable to the democratic regime; as well as those that intend to destroy it, along with its republican institutions; preaching violence, arbitrariness, disrespect for the Separation of Powers and fundamental rights, are not constitutional”.

The minister who ordered Silveira’s imprisonment is not the only one who agrees that the congressman’s manifestations in the published video exceeded the limits of freedom of expression. Carlos Ari Sundfeld, professor of Public Law at FGV-SP said that the attacks and excesses of the video, especially in the political context in which we are living, tend to configure a “verbal terrorism with the deliberate purpose, and the ability to seriously affect institutions.

The Counselor of the OAB (Brazilian Bar Association) Ana Carolina Moreira dos Santos also spoke out and said that, for the public interest and common good, the maintenance of the constitutional order should prevail when it is at stake with the guarantee of freedom of expression.

Silveira’s speech in his almost 20-minute video, therefore, goes beyond the constitutional meaning of the use of freedom of speech and hurts constitutional principles. According to Moraes, the Federal Constitution of 1988, in order to preserve democracy and the rule of law, does not allow the propagation of ideas that threaten the constitutional order or the democratic state, “nor the holding of demonstrations on social networks aimed at breaking the rule of law, with the extinction of the constitutional stony clauses – separation of powers (CF, Article 60, § 4), with the consequent installation of the arbitrary.

Thus, the deputy, who has already been accused of other antidemocratic acts, would have practiced acts that hurt Law No. 7.170/83 (National Security Law), which typifies crimes that “injure or expose to danger of injury” national sovereignty, the democratic regime, the rule of law, or the heads of the Union’s powers. Despite being a law passed during the dictatorial period, it is the norm that, filtered constitutionally, aims to regulate, at the moment, art. 5, inc. XLIV, of the 1988 Constitution.

In view of the justifications for Daniel Silveira’s imprisonment and the statements of professionals in the field about the deputy’s case, we realize that Silveira’s manifestations exceeded the limits of freedom of expression because they were considered a threat to the rule of law in view of the content of the published video. Since in the video the deputy called for Army intervention against the STF, for the return of AI-5, and for a coup against the democratic order, it was decided that the protection of democratic institutions and the institutional order should prevail.

Parliamentary immunity as a shield for deputies and senators

Article 53 of the Federal Constitution provides that deputies and senators are inviolable, both civilly and criminally, for any of their opinions, words and votes, being the STF responsible for their judgment, and that parliamentarians cannot be arrested except in the act of committing a non-bailable crime.

This legal provision is a prerogative of the parliamentary function and its purpose is to ensure the freedom of the representative in the National Congress, as a guarantee of the independence of parliament itself and of its existence. This prerogative is called parliamentary immunity, because it excludes the congressman from the incidence of certain general rules.

However, it is important to point out that immunity is not provided to generate a privilege to the individual who is in the performance of a parliamentary mandate, but aims to ensure the free exercise of this mandate and prevent threats to the functioning of the Legislative Branch.

Session for voting on legislative proposals. Deputy Daniel Silveira (PSL – RJ). Photo: Michel Jesus/Camera dos Deputados

The civil and criminal inviolability of deputies and senators for their opinions, words and votes guarantees the neutralization of the deputy’s responsibility in these spheres, but since immunity has a limited scope, in view of its objective, it is understood that the deputy’s act, to be absorbed by the prerogative, must have been practiced in direct connection with the exercise of his mandate.

The STF believes that words uttered “outside the formal exercise of the mandate” are not protected by the immunity, which “due to the content and context in which they were perpetrated, are completely unrelated to the agent’s condition as a Congressman and Senator”. The court also points out that immunity is not restricted to the physical space of the National Congress, accompanying the congressman “outside”, provided that the congressman’s actions are part of behavior that is an expression of the parliamentary duty.

If this does not occur and there is no relationship between the words and the exercise of parliamentary duties, the congressman or senator will be treated as any other citizen, being held accountable for what he or she said in all legal spheres, and the immunity provided in article 53 of the Constitution will not apply.

Thus, no one can hide behind parliamentary inviolability to, without any connection to the function and under the argument of freedom of expression, offend, slander and defame someone or spread hate speech, violence, discrimination and attacks on democracy.

In this context, after the determination of Daniel Silveira’s imprisonment, the House of Representatives, feeling attacked and threatened by the STF, organized itself to propose a PEC (Proposal of Constitutional Amendment) that aims to regulate Article 53 of the Federal Constitution. It is an attempt to extend parliamentary immunity and reduce the chances of imprisonment of deputies and senators.

In view of such PEC, it is worth questioning whether it would represent an attempt to expand the “privileges” that parliamentary immunity grants to members of Congress, excluding the possibility of accountability for their words in any context, which would challenge the limits of freedom of expression and what impacts this could have on our democracy.

By Ester Wagner Siqueira [1] and Rafaela Maria Cantídio Toledo [2].

For more information:

- Understand Daniel Silveira’s arrest, the Supreme Court’s decision and what happens now in the House of Representatives

- Brazilian democracy under threat

- Understand the Proposal of Constitutional Amendment the so-called “PEC of Immunity

- The legal dilemmas and the political effects of Daniel Silveira’s imprisonment

[1] Undergraduate student of Law at UFMG and extensionist of the Center for Transitional Justice Studies (CJT/UFMG).

[2] Law graduate from PUC Minas and extensionist of the Center for Transitional Justice Studies (CJT/UFMG).