This text intends to be a guide that seeks to highlight a relevant part of Brazilian documentaries that help us think about transitional justice in Brazil. It is important to emphasize that this is a selection based on films that have circulated not only in film festivals and exhibitions, but also distributed in the circuit of screening rooms, digital platforms, and television channels. The list below has more than 30 titles and is divided by sets that address agrarian, indigenous, quilombola, and civil-military dictatorship issues, with emphasis on productions made after the implementation of the Truth Commission Law, in 2011, and the opening of the dictatorship archives.[1]

Reflecting upon Transitional Justice – A guide to Brazilian documentaries

Reparation of the Krenak indigenous people for the violations suffered during the Brazilian dictatorship

During the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship (1964-1985), many indigenous peoples were targeted by the State’s economic development policy and the repression that, through land invasions, forced labor, compulsory displacement and other violations caused death and suffering to numerous communities. According to the Final Report of the National Truth Commission (CNV), at least 8,350 indigenous individuals were killed as a result of the direct action or omission of state agents. However, the Report itself recognizes that the actual number of indigenous deaths in the period must be exponentially higher, as data are scarce.

Electoral reforms: between the democratic rule of law and its erosion

On August 10, the House of Representatives approved, by 339 votes to 123, part of the basic text of the Proposal for Amendment to the Constitution (PEC) 125/11, which provides for profound changes in the Brazilian electoral system. A week later, the proposal returned to the plenary and was approved in a second round, being sent for deliberation in the Senate.

The Brazil of Backsliding: deliberation on printed ballots and military parade

On August 10, Brazil experienced another episode of what historian Lilia Schwarcz has characterized as a “theater of power”. On the same day that the vote on PEC 135/19, known as the PEC of the printed vote, was scheduled to take place, the Ministry of Defense held a parade of armored cars in front of the National Congress. The purpose of the event was to deliver the invitation for Bolsonaro and Minister Walter Braga Netto to accompany a traditional Navy exercise, known as Operation Formosa, which took place on Monday, August 16, 2021. The Operation takes place annually since 1988 in the city of Formosa/GO.

Borba Gato and the disputes over the country’s identities and memories

It was Saturday, July 24, 2021, when a group of young people dressed in black arrived in a truck and started to throw tires, spill flammable liquid on a statue that stands in the neighborhood of Santo Amaro, in the southern part of São Paulo, and set it on fire. Immediately, the media reported that the statue of Borba Gato had been set on fire. Authorship of the act was claimed by the group Revolução Periférica, which posted images of the action on social networks. In these same social networks an intense debate emerged about the legitimacy of the action. Some were against and others in favor. This is not an isolated fact in Brazil, much less in the world, especially regarding the connection of these monuments with modern slavery.

Brazil is losing the ‘war against Covid’ under the command of Captain Jair Bolsonaro – What is the role of the army in this ‘conflict’? And what lies ahead to Brazilians?

The Covid pandemic has often been described by the government in Brazil as a war both literally and metaphorically. While President Bolsonaro himself, a former captain of the army, often argues that it is a biological war launched by China, high-ranking members of the executive and legislative usually use it as a metaphor.

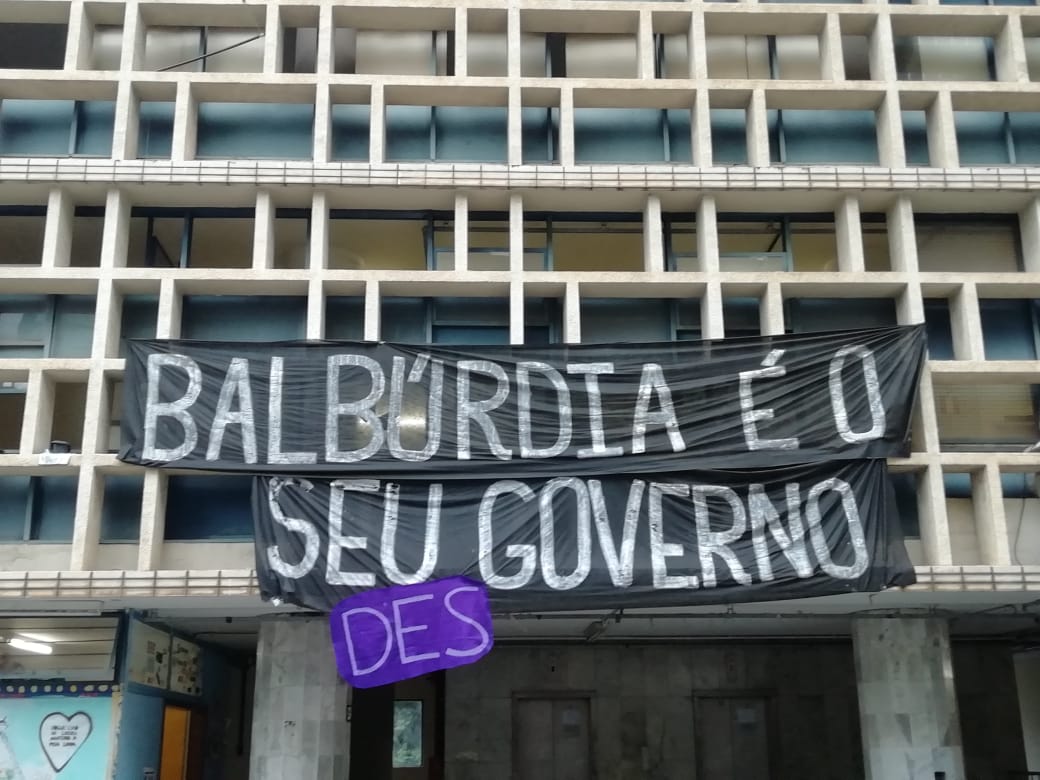

Dismantling of education: the anti-intellectualist policy under the Bolsonaro government

Since the beginning of the Jair Bolsonaro government, the system of higher education was pointed as one of the main theme that would be changed. In January of this year, Ricardo Vélez Rodríguez, then Minister of Education, said that universities would not be for everyone, but only for an “intellectual elite.”

Collecting polemics in office, Rodríguez was fired. In his place, the president appointed Abraham Weintraub. On April 30, the new Minister of Education announced the retention of 30% of the funds allocated to three federal universities: University of Brasilia (UnB), Fluminense Federal University (UFF) and Federal University of Bahia (UFBA).

According to Weintraub, the measure would be justified because these universities would be promoting “fuss”, allowing the realization of political events, partisan demonstrations or inappropriate parties. For him, these institutions were spending “money to make a mess and ridiculous events”, such as: “Landless [Landless Workers Movement (MST)] inside the campus, people naked inside the campus”.

Ensuingly, the measure was extended to all universities and federal institutes of education of the country, to the argument that “the budget cuts were operational, technical and isonomic”, due to the contingency of resources determined by the government through the Decree No. 9.741/2019.

In the same week (26), the president suggested that he study to cut investments in humanities courses at universities, especially in Philosophy and Sociology, in order to “focus on areas that generate an immediate return to the taxpayer, such as veterinary medicine, engineering and medicine”. On May 8, it was the turn of postgraduate research funded by CAPES (Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level Personnel) to be affected.

Although it has promised to invest in basic education, the current cut promoted by the government does not only reach universities: R$ 2.4 billion that would be earmarked for high school education programs were blocked. This blockade is larger than that of federal universities, whose value is R$ 2.2 billion. If materialized, such contingencies can lead the education system to collapse.

More than technical issues, these measures have a strong authoritarian content.

Anti-intellectualism

In “How Fascism Works: the Politics of Us and Them” (2018), Jason Stanley points to several of those that might be considered fascist policies – strategies that aim to consolidate a narrative that justifies the adoption of an authoritarian stance.

One of these policies is referred as anti-intellectualism, that is, the promotion of attacks on universities and the educational system as a whole, in order to remove their credibility and disarticulate resistance in these spaces and, consequently, in society. In this sense, the objective of anti-intellectualism is to devalue critical and independent education in order to avoid any threat to the implementation of ultranationalist guidelines.

The attempt to undermine the credibility of universities and educational institutions is consolidated in the representation of these spaces as places of violence, repression and bustle – in other words, “fuss.” Another common assertion of fascist politics is that the university only allows freedom of expression when it comes to left-wing discourses, that is, “indoctrination.”

Moreover, it is clear that certain disciplines and areas of study, usually historically focused on questioning the status quo, such as the Humanities, are the target of anti-intellectualist delegitimization, which goes from cutting funds to the persecution of teachers.

In the Bolsonaro case, his Plan of Government already contemplated the allusion to the existence of a “strong indoctrination” in Brazilian education. This kind of thinking supports Weintraub’s claim that students have the right to film teachers during their classes, in addition to the budget cuts already mentioned.

Attacks on universities are also accompanied by a broader campaign of disarticulation involving the basic education. This campaign has in the figure of educator Paulo Freire its main enemy. The current government has defended the need to extinguish the “Paulo Freire method”, although it does not clearly explain what it means by such a method, but let it anticipate the fight against teaching that promotes a critical view of the reality in which the students are inserted.

In this opportunity, Bolsonaro stated that he will withdraw from Paulo Freire the title of patron of Brazilian education. Although it may seem only symbolic, this measure evidences a broader attempt to establish the country’s education on new bases that are more reminiscent of the old and so called Brazilian Military Literacy Movement (MOBRAL), which functioned as an open opposition to Paulo Freire at that time.

The aim of all these actions of dismantling public education is not obscure or disguised, on the contrary: the president himself stated that “we want kids not to be interested in politics.” However, public schools and universities are places of production of knowledge and critical debate par excellence, aiming at the full development of the society and its preparation for citizenship, as, moreover, determines the Constitution itself, in its article 205.

According to Stanley, this lack of interest in politics is fertile ground for there to be no reasoned public debate and fascist leaders manipulate the narrative, forging a reality through destructing spaces of information such as universities. The problem with the creation of a parallel reality is that it can legitimize ultranationalist actions that, through a discourse of “us vs. them”, violate rights of minority groups.

The attack on universities is not a Brazilian prerogative. In Hungary, Victor Orbán pressed the European Central University, leading it to move its campus to Austria. A well-known Polish jurist, Wojciech Sadurski, is facing three lawsuits brought by the PiS (Law and Justice) party government from critical political statements published on Twitter. The Hungarian and Polish governments have repeatedly been criticized for the authoritarian manner in which they have behaved recently. In turn, the Brazilian government intends to strengthen relations with these leaders.

Responding to the dismantling of education

The budget cuts were heavily criticized. In the Senate, Senator Angelo Coronel (PSD-BA) submitted a request (REQ-CE 44/2019) to the Education, Culture and Sports Commission in which the Minister of Education is summoned to clarify the blockade.

In the Chamber of Deputies, the Education Commission is considering taking measures against the act practiced by Weintraub. On the other hand, Deputy Áurea Carolina (Psol-MG), presented a draft of legislative decree (PDL 215/19) to suspend the effects of Decree No. 9.741/2019, that brought contingency to discretionary expenses of the federal government and substantially affected the Ministry of Education, with a blockage of R$ 5.840 billion.

Sectors of civil society and several federal universities have spoken out against the measure, which may lead to paralyzation of activities and suspension of payments for water, electricity, cleaning services and acquisition of materials. The Parliamentary Front for the Valorization of Federal Universities defended, in a note, the autonomy and freedom of academic expression in Brazil. Academics around the world have also criticized president Jair Bolsonaro’s claim to cut funding for Human Sciences courses in Brazil.

A request for measures to investigate the possibility of administrative impropriety by minister Abraham Weintraub was filed, as well as filed lawsuits by parliamentarians and political parties before the Brazilian Supreme Court against the federal government’s decision to block funds from universities and federal institutes of education.

All initiatives are based on the same premise: to consider freedom of information, expression and circulation of knowledge “fuss” means preventing public debate and putting at risk democracy and academic freedom (article 207 of the Constitution). Public, basic and higher education should not be curtailed, so that budget cuts are extremely harmful to the social, economic and political development of the country.

More Links (in English):

Brazil plans to slash funding of Universities by 30 percent.

Students in Brazil protest against school budgets cuts.

By Almir Megali Neto [1], João Teófilo [2] and Sophia Pires Bastos [3]

[1] Researcher at CJT/UFMG. Master’s student at UFMG. Scholar by CAPES.

[2] Doctoral’s student at UFMG.

[3] Researcher at CJT/UFMG. Master’s student at UFMG.